“Géricault was one of those rare artists who changed the course of art not by refinement, but by force.”

— Charles Clément, Géricault: Étude biographique et critique, 1868

“He brought into art a new sincerity—violent, uncompromising, and profoundly modern.”

— Jules Michelet, 19th-century art criticism

Théodore Géricault (1791–1824) occupies a pivotal position in early nineteenth-century French art as a founding figure of Romanticism whose work bridged the traditions of narrative painting and the emerging demands of modern realism. His short, intense career was marked by courageous authenticity, emotional commitment, and a refusal to accept the prevailing conventions of artistic propriety.

Although Géricault received about three years of formal studio training—most notably with Carle Vernet and Pierre-Narcisse Guérin—he was largely self-directed. He copied Old Master paintings extensively in the Louvre and undertook formative travel to Italy, where encounters with Michelangelo’s sculpture and the dynamism of Baroque art profoundly shaped his understanding of anatomy, movement, and expressive scale. These experiences fostered an art grounded in physical intensity and psychological immediacy.

Géricault’s art is defined by its synthesis of Romantic drama with relentless observation from life. This fusion reached its apex in The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19, Louvre), a monumental painting that transformed a contemporary political scandal—a shipwreck attributed to governmental negligence—into a modern narrative painting of unprecedented realism and emotional power. In preparation, Géricault constructed a scale model of the raft, conducted anatomical studies of severed limbs and cadavers, and enlisted friends, including Eugène Delacroix, as models. The resulting work shocked audiences with its unidealized bodies, moral ambiguity, and direct engagement with current events, securing Géricault’s reputation while provoking intense controversy.

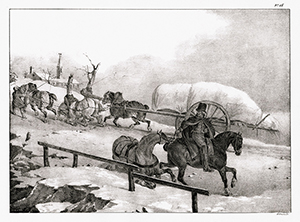

Géricault was a master of lithography, the only printmaking medium he employed. His lithographs, devoted primarily to horses and military subjects—lifelong passions—demonstrate the same immediacy and structural power found in his paintings. During his English sojourn of 1820–21, he deepened his technical understanding of lithography in the London workshop of Charles Joseph Hullmandel. The most significant outcome was the series Various Subjects Drawn from Life and on Stone (often called The English Set), a group of twelve lithographs notable for their fluid draftsmanship and dramatically composed realism. After returning to France, he continued his equine studies in the celebrated series Études de chevaux lithographiés (Studies of Horses in Lithography), which remain among the most accomplished lithographs of the Romantic period.

Géricault’s life was cut short at the age of thirty-two, following a prolonged illness resulting from a riding accident. His final major works—intimate portraits of the mentally ill, discovered decades after his death—extended his challenge to artistic convention by presenting marginalized subjects with dignity, gravity, and psychological depth. Like The Raft of the Medusa, these works redefined the boundaries of serious art and anticipated later developments in realist and modernist practice.

Géricault’s lithographs and works on paper are held in major public collections worldwide, including the Alte Pinakothek, Munich; Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum; Getty Museum; Hermitage Museum; Kunsthalle Hamburg; Louvre Museum; Metropolitan Museum of Art; Morgan Library & Museum; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon; Musée Fabre; Musée Royal des Beaux-Arts de Belgique; National Gallery of Art; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.